In our crowded country we simply haven’t the space for everyone to have a garden, so why shouldn’t we have gardens for everyone ?

I have a dream. I want to see our cities set amongst beautiful countryside managed for people, for wildlife, for a better quality of life for city dwellers. It’ll be community woodlands, nature reserves, reedbeds and meadowland open to everyone. Behind the pretty facade this apparently lazy land will be working hard – a key weapon in the fight against obesity, getting kids out from behind their computers and adults walking again. It’ll be absorbing the first shock of increasingly frequent floods, cleaning grey water through reedbeds, reeds which, with wood from the forests, is carbon lean fuel for the nearby town. People will cycle and walk to work on the comprehensive car free network of walking and cycling routes.

But most significant of all is the impact it will have on our success as a nation: do we want to become a low rent low income backwater, famous for the carelessness of our approach to our environment ? Or do we want to be a safe and attractive place for inventive, imaginative leaders of world business to live and locate their investment ? In a time of austerity it’s not even a choice that will cost: this is about having the imagination to see a different future. And the foundations are already there: we actually already know how to do it.

We started in 1947 with the planning act that introduced Greenbelts: after the sprawl of the 1920s and 30s a visionary Government was determined to stop our cities agglomerating into one big, scruffy blob. The Greenbelt remains as vital and relevant today as it was then – and it has worked. But the Greenbelt has been a largely negative tool. For many, its preserved green countryside on their doorstep but in some places like the Thames Gateway permitted development – mineral working, landfill supported by horsy culture, scrap metal yards, fly tipping and so on – has combined to produce a perfect storm of dereliction. In the north the remnants of mining and heavy industry blight whole landscapes. These are not nice places to live: quality of life isn’t an abstract when there’s a smelly, noisy landfill at the bottom of your garden or your house is overshadowed by a 200 foot high black hill.

But there is already an answer: over the last decade environmentalists have been transforming some of our worst landscapes, RSPB the Woodland Trust, the Wildlife Trusts, the Forestry Commission, the Community Forests, local authorities, the Regional Development Agencies and Groundwork.

After a long battle the RSPB won Rainham Marshes in the Thames Gateway for nature and in the process created a new vision for the urban fringe: they’ve proved you can have nature right next to where people live and work.

A school group learn about nature on their doorstep at RSPB’s stunning Rainham Marshes reserve in the Thames Gateway. Eurostar passes to the right of the picture.

It is possible to go from steel shedded industrial estate to natural grassland, lagoons and birds in one step: there is no need for the band of dereliction that defines too many of our urban edges today. Now children can be inspired by nature without a coach ride and it can be part of real life, not a treat. And best of all its possible to spot a Little Egret from a speeding Eurostar: could that be close to a definition of the civilisation we should be striving for in the 21st century ?

Not much more than a mile away the Forestry Commission has transformed a landfill into a community wood at Ingrebourne Hill. At the cutting edge of design, wildlife rich pools from previous mineral working are preserved, it’s not just about trees with extensive wildflower meadows and family cycling, a mountain bike skills track and a fibreglass climbing ‘rock’ are pulling in adults and kids. It’s a real doorstep wood: there’s a row of houses on one side of Avelon road, the wood on the other. This is in a place where people actually welcome a housing development next door because it means there won’t be an industrial estate or, even worse, a landfill site.

Individual projects are great but what is really exciting is the way, quite quickly, they can develop into something bigger. The Gravesend area is a good example. When the Forestry Commission bought Jeskyns Farm it found the Woodland Trust’s Ashenbank Wood as its direct neighbour and it neighbours Shorne Country Park to the north. To the east Cobham Hall is a Repton landscape under restoration whilst east again is Plantlife’s Ranscombe Farm reserve and it links into largely unmanaged woodland within the North Downs AONB. To the north east is RSPB’s Cliffe Marshes and subsequently has taken over over the foreshore towards Gravesend, only a few fields from linking with Shorne Country Park.

The biggest barrier is simply that each organisation is seeing its contribution in isolation: in the latest Birds Mike Clarke rightly celebrates their Futurescapes project to restore vast expanses of intertidal habitats in the Greater Thames – but makes no mention of the scale building up with the equal area of community woodland the FC has developed, almost linking together in places like Rainham and Shorne. Nor the fact that those woods can work with conservation to manage visitor pressure away from sensitive wildlife through scale and route planning, not keep out signs. We are on the edge of something much bigger: why shouldn’t the Woodland Trust’s Joydens Wood on the very edge of London one day link to Gravesend and beyond into the North Downs AONB ? Wouldn’t it be incredible to be able to cycle from London into real, deep countryside through attractive, car free countryside ?

But how do you afford it ? Huge amounts of money flow around any major development. And so does land. The Hampton development near Peterborough had far more land than it had permission for – but no clear after use. There was no vision. The Developers wanted to do the right thing and were frustrated that no one could give them a clear lead. In contrast at Greenham Common airbase the ‘brownfield’ built up bit of the base was sold by the Government for development but the runways and surrounding grasslands have been transformed into a superb nature reserve.

A clear vision gives everyone a lead – who knows what developers and environmentalists in partnership could achieve together ? Something, I believe, far more than simple ‘mitigation’. One absolutely key issue is cost: developers are used to high urban costs and tend to multiply them up – and can be exploited into ridiculously expensive landscaping schemes. Community woods and nature reserves are usually massively, maybe 10 times, less costly than urban landscaping and increasingly, rather than transforming landscapes, we’re all working with them – recognising that some features of even damaged land are wildlife rich and worth maintaining intact.

There may be cash savings to be made, too. We’re only just starting to explore ‘soft’ water management – using the natural environment more to absorb flooding, both downstream and surface water: a lot’s been done to develop ‘porous’ urban landscapes, but the potential of close to urban green space is in its infancy. Not only could space save money, but carbon as well – less concrete, reeds cleaning water that otherwise would have required energy. Trees and reeds may be there for people and wildlife but they need management – woods get dark without thinning, shading out wildflowers and less friendly for people and reedbeds dry out and turn to woodland, so to look after our environment we need to take the carbon out – and then we can use it, hopefully as close to its source as possible.

So, back to the Dream. Everyone knows they never come true.

Or do they ?

Back in 1996 I stood on top of Sutton Manor Colliery with Chris Robinson from the Forestry Commission, Tom Ferguson from St Helens Borough Council and Richard Sharland from Groundwork St Helens. We agreed the Forestry Commission could help develop St Helen’s ‘Wasteland to Woodland’ vision by taking on big sites like Sutton Manor. That day I privately decided our test would be what happened to the houses opposite, half of them boarded up. This is the land demolished empty houses, a million miles away from the over-heated Thames Gateway. St Helens has suffered a massive reduction in population over the last 50 years.

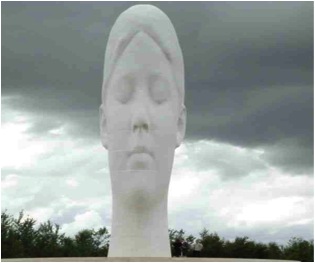

15 years later, on the very same spot, is Dream. Dream is a stunning, 20 metre high landmark sculpture by the Spaniard Jaune Plensa, poised above the busy M62 between Liverpool and Manchester. Ex Sutton Colliery Miners were the leaders who made it happen. It is the head of a young girl with her eyes closed. It is about looking into the future, for St Helens as it rises phoenix like from its industrial past, but for me it’s about much more: it’s a national message about how we can make this country a better place to live in the 21st Century.

And the houses ? Well, they’ve all got new windows and are being lived in and they’ve been joined by a new private estate right opposite the old colliery gates.

Not the best time for big ideas ? Well, Government’s opened the debate about planning and there is a need for change – so why can’t we make it our positive change ? At a fractious time when national morale is low coming together around a vision of a brighter future is what leadership is about. And we’ve got not just the planning debate on the go, but another bite at the cherry in the shape of the Independent Forestry Panel. That’s why I’ve written to several leading members of the panel suggesting they unite around a vision for ‘ a garden for everyone’.

Roderick Leslie Retired head of policy at the Forestry Commission, Rod worked for the FC for over 35 years. In his time as a forester, he not only worked in Field management & Conservation policy but was also the commission’s Private forestry & Environment officer for the South and West of England.

Rod is a keen ornithologist and expert on the critically endangered Nightjar. His book ‘Birds and Forestry‘ (co-authored with Mark Avery, ex-RSPB Conservation director), is acclaimed as a step toward sustainable forestry planning. Tackling the issues between forestry and nature conservation.Rod is a founder member of Our Forests!

The NPPF has the potential to make it harder for local communities to protect their green spaces from development. Learn more here: www.saveourwoods.co.uk/category/nppf/

You can help keep the pressure on government ministers by supporting the National Trust and the CPRE campaigns.

Don’t forget, if you’re on social media to share these links with your friends and followers and tweet your questions/comments about the NPPF using the #NPPF hashtag.

*There is a public consultation on the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) that ends on the 17th October*

This is OUR landscape!