Chris is an arboriculturist who has worked as a planning officer for Epping Forest District Council since 1989, with responsibility for tree protection and landscape issues. He had previously been a local authority tree manager and a tree surgeon in public and private practice. In this article he looks at the opportunities for Local Planning Authorities (LPAs) to use soft power, i.e. encouragement and persuasion in partnership with local communities to protect trees and increase tree planting in their areas.

Epping Forest district is situated in Essex to the immediate north east of London, is mostly metropolitan green belt, and is divided into 24 parishes. The settlements range from towns, such as Epping itself, Chipping Ongar and Loughton to villages set in open countryside, such as Roydon, Stapleford Abbotts and Theydon Bois.

Introduction: The Value of Trees

In many central areas of our cities the density of buildings means that the majority of the greening is in the streets and parks and so under the direct control of the local council. Here the issues of concern are not usually to do with the control of tree felling or pruning but include how effectively councils reflect the wishes and involve their communities in the way they manage their trees and how well they use their resources to increase the value of the tree stock over time. My own CAVAT method of placing a monetary value on urban trees, which I have developed over the last decade with assistance from the London Tree Officers’ Association (LTOA) and others, is intended to be a contribution to this second issue. At an earlier stage it was reviewed for the major official review of the state of play of the nation’s trees, Trees in Town II, and found to be a suitable basis for rational auditing of the management of the urban tree stock. Another important recent initiative aimed at increasing the understanding of the importance of urban trees is i-Tree. i-Tree calculates the financial value to the community of the quantifiable work done by its tree population, for example the cleaner air that results from the presence of large trees in urban areas. The results of a trial in Torbay have recently been published as Torbay’s Urban Forest. CAVAT and i-Tree may be used together as an aid to a councils’ tree management.

Conventional Tree Protection

However in most urban areas a significant proportion of the tree population is in gardens or informal green spaces, and not managed or controlled by the local council. This is the main focus of this article. The UK has probably the strongest system of protection of trees on privately owned land through planning powers anywhere. The Tree Preservation Order (TPO) legislation is well known, but of course tree protection is also inbuilt into the legislation safeguarding conservation areas and most statutory local plans have strong tree protection policies aiming to ensure that trees are protected during development and requiring new trees to be planted, along with more general landscaping.

What more might be done? Firstly TPOs work negatively, not positively. They provide no incentives to better tree management or care, only penalties for failure to comply with the legislation. These make it a criminal offence with potentially serious penalties to undertake pruning or felling of trees without permission. In reviews of the TPO legislation previous governments have however consistently resisted suggestions that it would be beneficial to give powers to LPAs allowing them to require owners to look after their preserved trees better. Secondly in most areas the majority of trees are not legally protected in any case, and legal protection comes at a significant cost in terms of the time required for the making of orders and their subsequent administration.

However that still leaves room for an LPA also to take a partnership approach, using means that do not depend on legal enforcement. Given that enforcement of TPO law is hit and miss, because many possible offences go un-noticed and even when detected are difficult to prove beyond reasonable doubt, it may be thought that there are potential advantages in this. The logical basis of this is that finding a variety of ways of increasing awareness of the importance of trees and allowing communities means of expression of their pride in their local trees should also be a form of tree protection. In a sense it would be protecting trees through allowing communities ways to express their common understanding of the beneficial effects of trees in their lives, rather than through a fear of penalties for breaches of the law.

Protection through Celebration

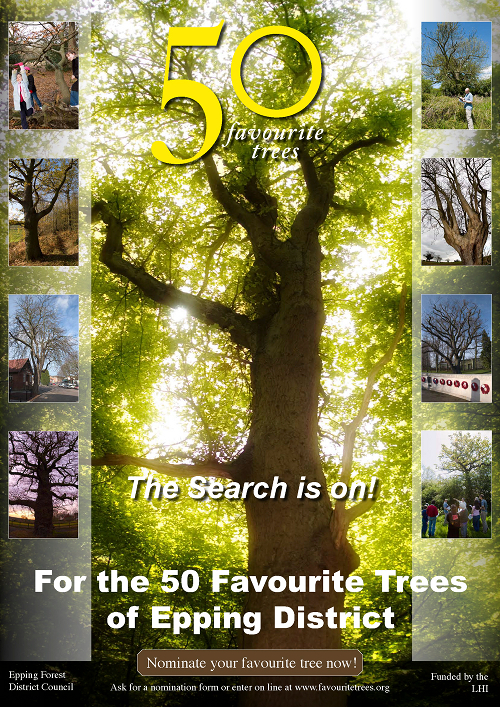

One way of doing this is engaging with the community in celebrating locally important trees. We have an initiative in Epping Forest District to designate favourite trees, which we started in 1995 and which was the pro-genitor for the Tree Council Millennium Project for the nation’s favourites.

It is possible to have a really rather extensive local project, if the resources are there to back it. For example, one of our parishes is Roydon. It is a village sandwiched between the urban areas of Hoddesdon across the river Lea in Hertfordshire and Harlow. To the west and north are meadows and willow fringed streams, to the east farmland, with ancient hedgerows and drove ways. In 1997 as a pioneer project we engaged the assistance of the parish tree wardens to consult their local community on their Landmark Trees (as we called the project at the time). Members of the public were asked for the location of the tree, a photograph, and an explanation of why it was important to them. The project was advertised through local media, newspapers, but also word of mouth. Perhaps the most important element was that the local school were involved which, of course, also meant that parents became aware of it.

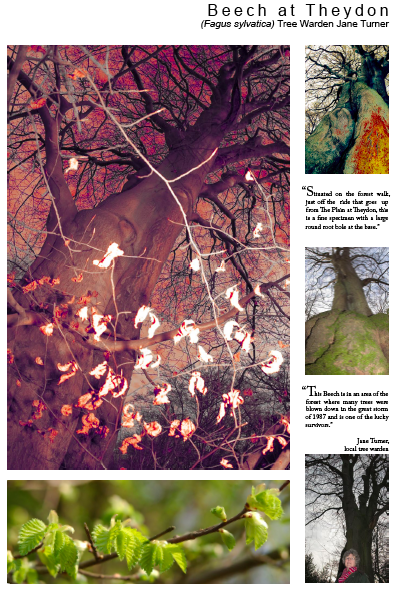

Tree wardens at an ancient "coppard" beech, one of the treasures of Epping Forest, and an inspiration for the Favourite Trees competition.

There was a good response. There were many nominations for the fine Horse Chestnut tree on the village green. Other nominations were more surprising including an excellent spreading medlar in a small front garden in a local housing estate, some wonderful veteran trees in local woodland, including a group of the rare female native black poplars. One of these later became a millennial “Great British Tree”. We moderated the nominations together with several of the tree wardens and “weeded out” some of the weaker entries, such as a rather undistinguished weeping willow, by agreement. At that time we had no website so the results were published conventionally. However, the project also extended to further work with the community.

Each of the trees was represented by a work of art by local people including children, small oil paintings, watercolours, but in some cases tapestries. These were then mounted on a large, painted map of the parish and were exhibited in various venues in the Parish. It now has a place of honour in the district council offices. Perhaps the most memorable part of the celebration of the project was a tree dressing project undertaken as part of National Tree Week, involving a torch lit procession to the tree from the school, the children dressed up as forest creatures and a speech by the Mayor, which ended with him “waking” the tree. The tree itself had been dressed with banners. Afterwards the grown ups and children together adjourned to the village hall for an evening of music and storytelling.

Partnership Working with the Community

The discovery of the black poplar cluster also led to a restoration project, led by the local resident and artist Alan Burgess, the tree warden co-ordinator for the parish. The condition of many of the poplars, mostly veteran pollards, was poor, as were their prospects for long term survival. A modest grant from the Local Heritage Initiative paid for a program of phased crown reduction of the pollards most at risk. This was completed successfully, with the support of the owners and an excellent local tree surgeon. The only casualty was one pollard, which broke in a gale before sufficient of the weight had been able to be removed. (This needed to be done carefully, in stages, to avoid compromising the health of the trees).

A second strand was an arts project with children from Roydon Primary School, focussing on these very special trees, helping to make a connection between them and their wider environment. Finally many more saplings have been established from cuttings from the local trees and planted throughout the parish. The most enthusiastic planter has proved to be the farmer Charles Abbey, whose Worlds End farm was where the first tree was found. When The Tree Council were scouring the nation for Great British Trees as their millennium project, Roydon was honoured that this first Landmark Tree at Worlds End Farm was selected. This project was later continued by the Tree Council as their Green Monuments initiative.

Did the Landmark/ Favourite Tree series of projects achieve its aim in Roydon? There is no doubt that it raised the awareness of the importance of trees in the village, at least for a period. For example the owners of the nominated trees were all consulted and they were assured that their consent was a pre-requisite for their trees to be included. This gave the opportunity for discussions and advice to be given. To my knowledge only one has been lost. Ironically that was the signature horse chestnut, a victim of butt rot by Ganoderma applanatum, (the Artist’s Fungus), despite efforts funded by the community and parish council to save it. However a fine new London plane stands in its place on the village green at the heart of the community and with luck for the next several centuries. The children who were a part of it all no doubt still remember and understand their environment a little more than they otherwise would have. Many more will have memory of the torch lit processions and the banners hung in the great horse chestnut. Roydon itself remains an attractive village, in pleasant countryside and retaining its own special identity.

However the project depended on circumstances that are not available everywhere, and also a degree of support that cannot be extended over a whole district. The advent of the internet as an almost universally available means of communication and the storage and dissemination of information gave another way of approaching the task. If you were to search for 50 Favourite Trees now you would now find a dedicated web site for a district wide Favourite Tree project, itself extended into a record for our ongoing veteran tree survey. So far we have found and recorded almost 3,000 of those. The web site’s search system is a little clunky, although we have been able to graft on a map based search which works better (once you find it). However, it gives us a cost-effective tool to continue with the initiative.

Another weakness, which could be said to apply to any freestanding project would be that it might be seen to lack a strategic basis, in other words there is no assurance that the issues it seeks to address are the most deserving of resources.

A veteran Wild Service Tree in a wood called Apes Grove, near Abridge, one of our 50 favourites from the district. (Photo credit: John Price)

Strategy, bottom-up!

By no means all council areas in the UK are covered by tree strategies at all and of those that do exist almost all concentrate on how best the particular council may manage its own trees. In cities or at the centres of major conurbations, as I mentioned earlier, this is less of a weakness because the majority of the trees that contribute most strongly to public well-being are in streets or on publicly owned land. However in less densely populated areas garden trees can often be an extremely important component of the treescape and not under the direct control of the council. Similarly in open countryside, other than parks or country parks, LPAs can generally exert only limited control through the planning process. By and large therefore these kind of conventional strategies, even where they exist, do not allow councils to influence the fate of the majority of trees in their area. The second issue is that, by and large, such strategies look at direct action by the council, not actions in partnership with others to influence indirectly.

The judging of the competition. Judging was moderated by Christopher Neilan (front right foreground) and Paul Hewitt (Country Care Manager, centre). The judges included David Jackman, then editor of the local paper (front left, foreground) and then Tracy Clarke of Tim Moya Associates, Mark Iley of Essex Biodiversity Partnership, John Hammerton and Tony Kirkham of Kew Gardens and John Stokes, Tree Council. (The latter 3 were filming their series, The Trees That Made Britain, and brought some friends!) Photo credit: John Price

What might be done about this? One possibility is to engage the local community in series of neighbourhood plans focused on trees and landscape. There are of course precedents for this kind of approach but generally aimed at heritage or townscape, rather than green infrastructure. Having joined the Tree Council’s Tree Warden Scheme in 1995 and beginning to work with tree wardens on projects such as Landmark Trees it seemed natural to try to generate a strategic context for such local initiatives. We called them Parish Tree Strategies and so far have undertaken five. Not unsurprisingly this includes Roydon but in order we have also joined with local communities in four of our other parishes, Stapleford Abbotts, Theydon Bois, Ongar and most recently Loughton.

In each case the aim has been to produce a strategy document and an action plan following consultation with the local community to list concerns, gather information, and later to test draft policies and the action plan. The underlying model for the documents was taken (imitation being the sincerest form of flattery) from the then Countryside Commission and specifically their series of landscape assessments. The Dedham Vale Landscape Character Assessment 1997 was particularly apposite, being a study of the background material and the mapped information, and including research into landscape change at the perception of landscape.

The structure that we derived from it was to:

- describe the history of the whole landscape/townscape and the trees etc it contains, explaining how it came to be as it now is and what are the main factors that have acted to produce it;

- describe and then assess the current landscape, both the countryside but also the green elements of the built up areas;

- set out the key issues, having carefully insured that the information necessary to understand them has been conveyed in the previous sections;

- set out the way forward, in terms of the key policies that need to be followed if the issues are to be addressed; and

- include additional informative material in the form of free standing paragraphs, where necessary.

Like the Countryside Commissions we have aimed to produce attractive and well illustrated documents, with an element of colour at least, but unlike their studies ours are consciously intended to be easily accessible for non specialists. The rigorous structure is adapted so as not to become a barrier to a general audience. In each case we have published an action plan, but separately to the strategy itself. The thinking here was that we intended that the main document should be valid for many years. The action plan of necessity would date and so would be best published and followed through separately.

The oldest timber framed church in the UK, and probably the oldest timber building surviving in the whole of europe- Greensted Church, Ongar. A real Essex treasure.

I well remember still the initial public meeting for our first tree strategy. This was at one of our more rural parishes, Stapleford Abbotts. I had spoken to the parish council at one of their regular meetings and had their support. They made available the parish hall for the first meeting and handled the publicity. They were very dubious, however, as to whether anyone at all from the village would attend. As it turned out the hall filled up and the meeting was lively and enthusiastic. We had a mixture of all sections of the local community including the head teacher of the primary school, schoolchildren, ordinary residents, but also farmers including the tenant of the largest farm in the area. He told us that he missed the visits of the local school children to his farm, and would welcome them again. In truth, I am not sure that that actually happened, but if so only because of the shortage of time in the modern school curriculum. Certainly the school itself is now a very green place with many more trees and a bower made of woven willow for the children to shelter from the summer sun.

Cllr Mrs Caroline Pond, Kevin Mason (Epping Forest Countrycare), Cllr and Tree Warden David Wixley, and Tricia Moxey, local resident and main author of the Loughton Community Tree Strategy at our stall at the High Beach Fayre, part of the community consultation exercise for the strategy. (Photo credit: John Price)

This process allowed us to understand in some detail the evolution of what proved to be a very special patch of countryside, right on the edge of London. It includes Albyns Deer Park. Albyns mansion itself had burnt down, other than its stables, but we were able to tell, briefly, the story of that landscape and also the evolution of the farmland around it. It turned out that there were particular issues that had been local bug bears for years, for example an area that had become used for illegal tipping. The issues preventing them being resolved had generally been a lack of awareness of their local importance or a lack of coordination between the various councils or agencies. The reality of the Parish Tree Strategy focused attention and enabled in each case a resolution to be achieved. Other outcomes were more strategic. For example, the initial surveys showed important veteran trees in Albyns Park; one of the actions that arose was to map the veteran trees throughout the Parish. To date we have recorded no less than 204 on the Favourite Trees Website.

Among the other interesting finds was that a major constituent of local hedgerows was elm. Where these had not been managed there were significant problems from Dutch Elm Disease. However, many of these hedgerows were being regularly trimmed and as a result were in excellent health. Single species elm hedgerows are of course an indicator of ancient countryside, which is what Stapleford Abbotts proved to be.

The first community to address one of our urban areas was that for Ongar. This was also the first to be published on the internet as well as in hard copy. In one way it is weaker than the others, unfortunately, because the analysis and policy section of the main document has been truncated. On the other hand there was still a comprehensive action plan which has been followed through.

Perhaps the most successful of these documents has been in Theydon Bois. This success has come from the fact that the parish council took responsibility for ownership of the action plan and was prepared to convene a working group to review annually the success of the previous year’s actions, and to update the plan on a continuing basis. This has led, for example, to a thorough review of the street tree provision in the village, problems with over-large and unsuitable trees having been dealt with and a major planting plan of more suitable species. The effect has greatly improved the quality of the street tree provision, and also its acceptability to local residents. As a welcome by product the relationship between the parish council and the district’s tree managers has become much more positive.

Another local issue that arose from the consultation was the matter of the historic avenue of oaks across the village green. There was a strong local view, registered in the consultation that the avenue, planted in the 1830s and some 250m long, was becoming tatty and had lost its unity. However, they were able to get nothing done. The Avenue was the responsibility of the City of London, in its guise as the Conservators of Epping Forest, the green being a part of the ancient forest. The green also contained areas of scrub, generated from root suckering from elms that had died some years before from elm disease. The community’s view was that these were unattractive and unsightly. Again, they had been able to get nothing done. Inclusion of these issues in the action plan set off a chain of events that allowed them to be resolved. The City of London agreed to grub up the suckers and I was able to design a replacement planting for these in the form of a roundel of groups of native trees. Even more significantly the conservators agreed to undertaken necessary management of the row of oaks, but also to plant a new avenue that they would manage in a uniform way outside it, something that they had originally been very reluctant to do. Again, it was fact that the community had a degree of ownership of the strategy that brought light and thought to bear on the problem, allowed the local community’s wishes and desires to be expressed and explored, and solutions found.

Conclusions

Are such initiatives necessary?

Clearly not, since the great majority of Councils do nothing along these lines.

Given the current hard times, particularly for local councils, are such initiatives realistic any more?

I would turn that on its head, to say that for councils to be far more community focussed is the way of the future. It can be seen as a way of making the “Big Society” happen, but enabled by local councils rather than bypassing them entirely.

Are they worth while?

Hopefully this article gives an idea of why I believe so, recognizing that they must be seen as complementary to more conventional tree protection. The new key phrase in planning policy for trees and landscape, invented by Natural England some few years ago, is “green infrastructure”. Green infrastructure is the jargon phrase for trees, hedgerows, meadows etc but designed to speak to those in power in the language they understand. They are used to the idea that money must be spent on infrastructure, such as roads and railways, so why not on green infrastructure? Green infrastructure policies are likely to frame conventional tree protection policies in our new draft district plan, currently in preparation, as in many others. This kind of conventional “hard” planning sits happily alongside community based initiatives. A conventional tree and landscape strategy will be more powerful sitting alongside and linked to community tree strategies that allow communities to express their wishes and have their valuations of their own countryside and urban treescape recorded, including the story of how it came to be what it is. After all it is a part of the story of their community.

by Chris Neilan,

Arboriculturalist and Principal Officer Landscape & Trees for Epping Forest District Council

———————————————————————————————–

Photo Credit

Christopher Neilan and Paul Hewitt (unless otherwise stated)

Acknowledgements

Further reference

1. Trees in Towns II, Case Study 9, Establishing and Justifying the Budget.

Chris Britt and Mark Johnson. DCLG Feb 2008.

2. The Dedham Vale landscape – a landscape assessment prepared for the Countryside Commission. Landscape Design Associates. Available from Natural England

Links to websites

The Roydon Black Poplar project

The Roydon Black Poplar book project

Great British Trees and Green Monuments

Community Tree Strategy for Ongar

I’m going to start using that term “green infrastructure”. The concept is clear. The idea is constructive in that we will be building, repairing, and adding to what already exists for the benefit of generations to come.

A very, very useful article. I am appalled at the lack of investment by councils into promoting trees, it seems such a simple and money saving exercise in the long term, (as well as a joint celebration of a shared place, which a tree is and is often used as the emblem of initiatives which then fail to move forward). Far too many cases end up in English legal system at huge costs to the taxpayer or subject to fines which developers can afford and which further diminish respect or engagement by the public. The two ways forward are 1: Comprehensive legal protection for all trees, which sounds good to many, but as Christopher hints at it could well be fatalistic and this simple, now proven, 2nd approach ‘Soft Power’, (a term I will also adopt at forthcoming meetings), will rattle no cages. It is a real solution. Thank you for highlighting. My day is now spent reading up on everything else on here posted since my last visit. Keep it coming ‘Save Our Woods’!

Hi Lesley. Thank you for such a positive comment. It is much appreciated. Chris

I echo Lesley’s comment. And have found myself on a few occasions recently using the term ‘Soft Power’ to an intrigued audience. The many locations I have cared to call home in England have had very varying LA attitudes towards trees in their care and if this as a case study can be pushed at every level then it will provide the connection between people and their trees, (and the wider landscape), that we all know is so sorely needed. Thank you for the article, a real eye opener.

{ 1 trackback }